THE STORY BEHIND THE BOOK: Agatha Christie and The Mystery of the Blue Train

Why did she hate this Poirot novel so much?

“Her mental illness of 1926 was nearly the breaking of Agatha Christie. But ultimately it was the making of her.

According to a friend, 1926 went so deep ‘it left its traces all through her work. It also made her the great woman she became.’”

Lucy Worsley in Agatha Christie: A Very Elusive Woman (published 2022)

My fascination with Agatha Christie has grown increasingly over the years. It all started with the murder mysteries I used to watch with my Nana when I lived with her during the summer after finishing university. They were what I call ‘cosy murders’ because they weren’t graphic and they didn’t leave you tense from rapid heart-beating psychological elements. The likes of Morse based in the beautiful city of Oxford, Inspector Frost could be a little bit darker, plus, of course, there are the ITV adaptations of Poirot with David Suchet. I was heartbroken after leaving a relationship, and these programmes, plus my Nana’s cooking, soothed my soul.

My nana lived in Marlow at the time, and she would’ve been thrilled that a new murder mystery series, The Marlow Murder Club by Robert Thorogood, would be written about and then filmed in the beautiful town.

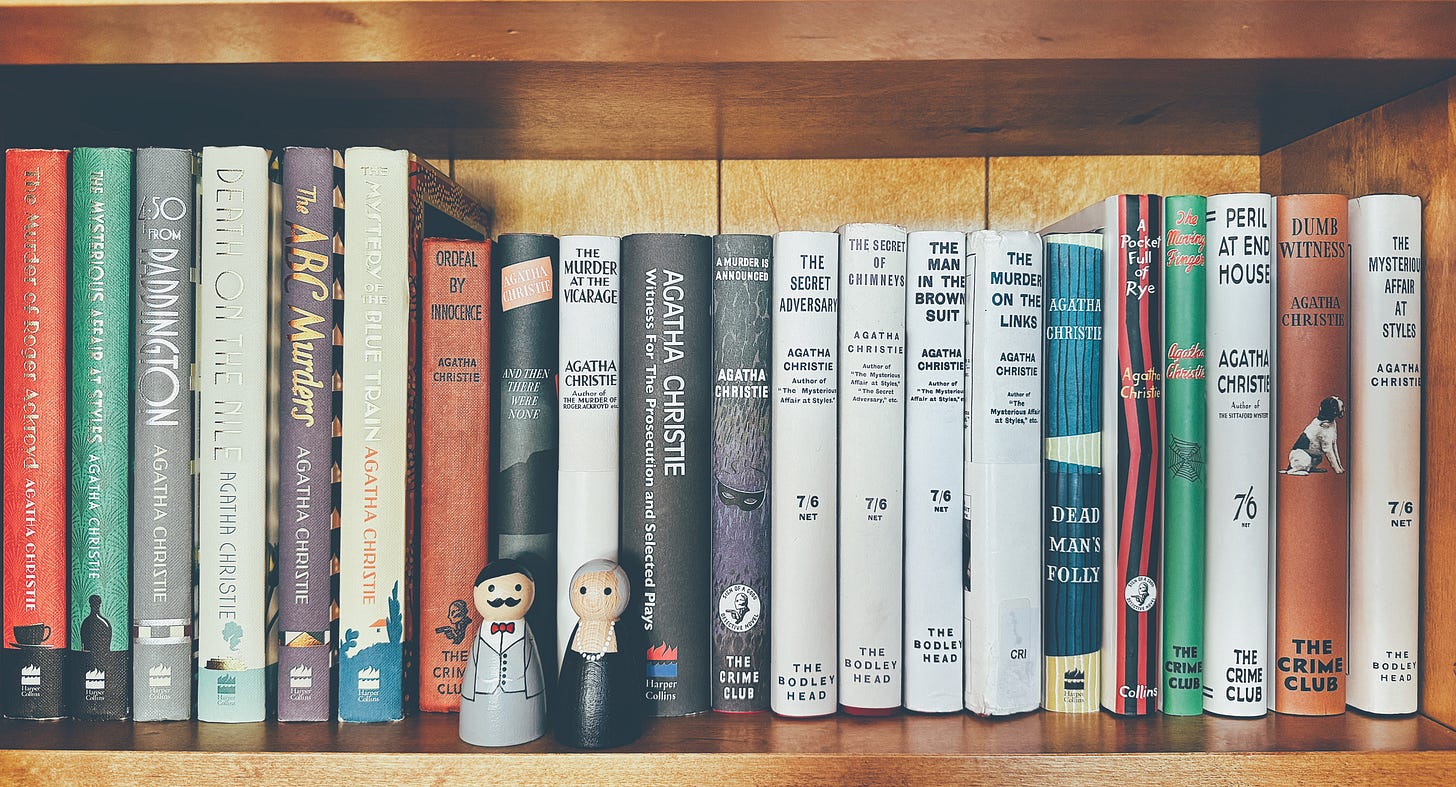

At Bertram’s Hotel was the first Agatha Christie novel that I read. Back then, I preferred the television programmes to the books, but over the years I began to read more. And I began to collect the books. I particularly love The Crime Club editions and the beautiful, more recent releases from HarperCollins with the stunning endpapers. I also have a couple of Folio editions, which have wonderful illustrations. This growing collection is my pride and joy. One day, I’ll treat myself to a signed edition.

Last year, I decided to start reading them all in chronological order. Basically so I wouldn’t miss any of them out and so I could see how Agatha’s writing developed over time. As I read, I wanted to know more about this incredible woman. How did she write? Where did she write? How long did it take her to write a book or a short story? How did she plan the books? So many questions. And thus, my fascination grew.

During a beautiful spring of 2013, when the trees were just coming into bloom, I travelled down to Torquay in Devon. I’d been invited to stay at The Imperial Hotel on the sea front of Torquay (where she has stayed and which has been mentioned, with a different name, in the novels The Body in the Library and Peril at End House by Agatha Christie) as part of a press trip. Our itinerary also included a trip on a steam train to Kingswear, where we’d board a boat over to Dartmouth, then board another boat up the River Dart to Greenway, Agatha Christie’s holiday home.

Greenway was beautiful. The bluebells were in full bloom, and we took a short walk down to the boathouse where my husband pretended to be murdered (this was actually where the 2013 ITV adaptation of Dead Man’s Folly with David Suchet and Zoë Wanamaker was filmed).

Alongside many others, we also took a tour of the house. It was fascinating (you can see a few photographs on The National Trust website), but once we’d moved upstairs and walked into her bedroom where we could see her clothing all hanging in a row, I turned to my husband. “This doesn’t feel right,” I whispered to him. “Let’s go.” Rather spookily, and this is not a regular occurrence for me, I’d had a very strong feeling that Agatha Christie wasn’t happy with so many people viewing her personal effects and intruding on her personal life.

The following day, I described this strange feeling to the tour guide. “Oh yes, she was incredibly private,” he said, not looking at all perturbed by the fact I’d felt her thoughts. In A. L Rowse’s essay about Agatha in his book, Memories and Glimpses, he describes her as “retiring and modest,” going on to say “she actually avoided publicity all she could, never gave an interview, or made a speech, let alone appeared on TV”.

The 1979 film Agatha, starring Vanessa Redgrave as the author, portrayed her as extremely shy around crowds of people. At a literary luncheon, when it was her turn to speak, she stood up and simply said “thank you.” Before sitting back down.

For someone so shy and so private, the media frenzy that resulted after her eleven-day disappearance in December 1926 must have been horrific. It was no wonder she fled to the Canary Islands a few months later to escape the attention so she could write her next novel, The Mystery of the Blue Train, in peace.

Ah, The Mystery of the Blue Train. That’s where the seeds of this essay began. I’ve read ten books so far in my ‘Agatha Christie in chronological order reading project’. Not a massive amount as yet out of the seventy-plus novels she wrote under the Agatha name and the Mary Westmacott name. She also has several short story collections, plays and an autobiography for me to read. Lots to dive into.

The seeds of this essay also began with TikTok. Because on there, I’ve been uploading short videos of me filling in my reading journal as a record of all the books I’ve been reading. And I also provide a voiceover reviewing the book. When it came to The Mystery of the Blue Train, I felt compelled to do a little research around it.

In the book Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Greatest Detective in the World, Mark Aldridge quotes Agatha as saying,

“easily the worst book I ever wrote was The Mystery of the Blue Train. I hate it.”

And I thought - why? It’s not the best novel of hers, but it’s also not the worst. But Agatha Christie looked down on people who said they liked it. She believed it was “commonplace, full of clichés, and that its plot was uninteresting.” But as Charles Osborne says in his book, The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie, where he defends The Mystery of the Blue Train,

“third'-rate Christie is, perhaps, to be sneezed at, but not second-rate Christie.”

It is quite possible that Christie hated The Mystery of the Blue Train so much because of what was happening in her personal life at the time. And because of what she had to do to fulfil her contractual obligations, even though she was struggling to write. The Big Four, Agatha’s previous novel (and which was published a month after her disappearance) was also a book she did not like and described as “rotten”.

It all started earlier in 1926 when her mother, Clara, died. Agatha was close to her mother, and even though she had bronchitis, Agatha had expected her to pull through. Agatha’s husband, Archie, was abroad at the time and didn’t return until after the funeral. Agatha, in her autobiography, recalls him saying, “I hate it when people are ill or unhappy - it spoils everything for me”. So, he simply avoids the person and the situation.

In fact, as Agatha went to stay at her mother’s house to declutter and empty it, he avoided Agatha and her sadness for some months. Agatha was on her own with her daughter, Rosalind, no other adults for company, and worked “like a demon” to get rid of everything. Ten to twelve hours a day, she worked. But she “began to get confused and muddle over things. I never felt hungry so ate less and less.” She asked her husband to come down but he refused citing the expense and work. Meanwhile, Agatha’s mental health began to unravel in an alarming way.

“A terrible sense of loneliness was coming over me. I don’t think that I realised for the first time in my life that I was really ill. I had always been extremely strong, and I had no understanding of how unhappiness, worry and overwork could affect your physical health.”

Agatha Christie in her autobiography (published 1977)

Agatha was lonely. She had no support. She was grieving. She was overworking, and she hadn’t been able to write since her mother died. She was probably worried she hadn’t provided for her new publishers after the huge success of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, and they had financial issues. All of her money had been spent on Styles, their house.

Then came the biggest bombshell. Archie had met someone else. And wanted a divorce.

Archie told her this in August. It’s interesting that Agatha, in her autobiography, appeared to blame herself. She believed he’d strayed because “he had missed his usual cheerful companion” and she writes “if I’d been cleverer, if I had known more about my husband…instead of being content to idolise him and consider him more or less perfect - then perhaps I might have avoided all this…if I had not gone to Ashfield and left him in London he would probably never have become interested in this girl.”

And so came to an end, over the next few months, that “happy, successful, confident” part of her life.

In her autobiography, she doesn’t refer to her disappearance. But she does allude to the fact she had a “nervous breakdown” - although officially, at the time, they said she simply lost her memory. Back then, mental illness was not something you publicised. Mental illness was also part of her family history - a few of her relatives had ended their own lives or spent time in insane asylums - and at a point soon, she’d want to get custody of her daughter.

At the same time as all of this, her next novel, due to be published in January 1927, had to be written. She needed the money, she writes, “I had no money coming in now from anywhere except what I could make or had made myself.”

Her brother-in-law and friend, Campbell Christie, helped her bring together the last twelve stories she’d written for The Sketch and create a novel from them, calling it The Big Four. Agatha states that “he helped me with the work - I was still unable to tackle anything of the kind.” I hadn’t known about this when I read The Big Four and remember thinking at the time that it read like a series of short stories rather than one cohesive novel. This explained why Hastings was constantly being set upon by the villains - if it were a novel, he wouldn’t have been hit and hurt so many times - but in each short story, you could get away with it. At the end of the novel, Poirot also states that he’s now going to retire and grow marrows. The timescale of this really confused me as the preceding novel, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, opened with Poirot growing marrows and retired. The short stories were written before The Murder of Roger Ackroyd though, so this now makes sense. (I do like things neat and tidy in the stories I read - very Poirot-esque).

In December of 1926, Agatha disappeared. Her mental health broke. Her car was found damaged - possibly because Agatha was trying to end her life, with her personal effects on the back seat. Her husband was contacted - he was spending the weekend with his friends and his mistress - and a manhunt was organised. It was suspected by the police that Agatha had either killed herself or been killed by her husband. They used the press to try and find her. Of course, when she turned up in a hotel in Harrogate eleven days later, the media were terribly disappointed that there was no tantalising death or murder mystery - thus the frenzy and the backlash.

There have been many theories as to why Agatha Christie disappeared. A film has been made about those missing days (Agatha, 1979), novels have been written with their theories, a television programme depicts Agatha as being involved in a murder mystery story, and Doctor Who even got in on the act, suggesting it was a shapeshifting giant wasp that was behind her disappearance.

In real life, there were also many theories. Has Agatha staged her disappearance to make her husband a suspect? Has she done it for publicity? I think the best explanation comes from the historian Lucy Worsley, who writes:

“On Saturday 4 December 1926, and for some days thereafter, Agatha experienced a distressing episode of mental illness, brought on by the trauma of the death of her mother and the breakdown of her marriage. Agatha’s experience encompassed more than just the ‘loss of her memory’. It was even more frightening and disorientating than that. She lost her way of life and sense of self.”

It is believed that Agatha was experiencing “dissociative fugue”, which is a state brought on by trauma and stress where you literally forget who you are. She even used a different name at the Harrogate hotel, calling herself the same name as her husband’s mistress “Neele”.

After this episode, she was referred to a specialist in psychiatric treatment in Harley Street. From there, she decided to travel to the Canary Islands with her friend plus her daughter. From February 1927, she started to write The Mystery of the Blue Train. She’d been through grief, abandonment, worry and a nervous breakdown. Plus, the subject of media speculation, both national and international, and hounded by them for months.

Her psychiatrist told her not to start writing. But she needed to. As Lucy Worsley writes, “it’s possible she found some solace in the imaginary world.” This reminds me of the short story, The Yellow Wallpaper, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, whose protagonist was ordered not to do anything creative whilst suffering with her mental health after the birth of her child. Which subsequently made her mental health worse. So I’m glad Agatha Christie disobeyed her doctor’s orders. I truly believe that creativity is something to be encouraged for those with depression. It certainly helped me.

Like The Big Four, The Mystery of the Blue Train was inspired by a short story. But this time, it was just the one, The Plymouth Express. Agatha took this story and expanded on it, basing it on a journey to the French Riviera instead of in England. The biographer, Laura Thompson, believes the character in it, Katherine Grey, “was balm to her shattered spirit”.

Thompson goes on to write,

“Throughout much of this book Agatha is talking to herself, reassuring herself about the divorce, allowing the integrity of her heroine to console her.”

Poirot also offers consoling words to Agatha within The Mystery of the Blue Train. When he was with a daughter of one of his contacts at a local spot known for suicides, Poirot says: “One is foolish to leave all that simply because one has no money - or because the heart aches. L’amour, it causes many fatalities, does it not?”

So The Mystery of the Blue Train could very much have been the novel that Agatha Christie wrote where she allowed herself to mend from the grief and the despair. Where she acknowledged that from now on, her life was going to be different. It was also a turning point for her as a writer. She now had to write as a professional, not just as a hobby, because she had to provide financially for herself and her daughter.

And, understandably, considering what she’d been through, it’s not one of her best. So, the self-criticism will be high.

But it was a life-changing novel. A painful life change. It was the full stop after the death of her mother, the abandonment and betrayal of her husband and her nervous breakdown being so publicly and humiliatingly examined. It was written after an intense public backlash.

She was, as I said right at the beginning, intensely private - yet everyone who could read now knew about her marriage breakdown and mental health battles.

No wonder she hated The Mystery of the Blue Train.

“But perhaps the greatest solace of all was the Blue Train itself. Murder scene it may have been, yet it bloomed in Agatha’s mind as a symbol of order and escape.”

Laura Thompson in Agatha Christie: An English Mystery (published 2007)

If you enjoyed this essay, I’d love it if you gave it a heart or a share. If you’re interested in the behind-the-scenes of how I came to write this essay, how long it took me to research and write, what mindset issues it brought up, and more, I’ll be diving into that for my paid subscribers next week. You can upgrade below:

FURTHER READING ON MY SUBSTACK

Down an Agatha Christie Rabbit Hole

REFERENCES

The Mystery of the Blue Train by Agatha Christie

The Big Four by Agatha Christie

Memories and Glimpses by A.L Rowse

Agatha Christie’s Poirot: The Greatest Detective in the World by Mark Aldridge

The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie by Charles Osborne

Agatha Christie: An Autobiography

Agatha, the film, 1979. (I rented and watched through Amazon).

(These links are Amazon affiliate.)

Fascinating! Really enjoyed reading this and the research shone through 😊

This is fun to read, and I’m intrigued by your read-in-order project. Are the Poirot and Miss Marple mysteries mingled together, if you do it that way?